Barry Gardiner and Suraj Kanwar

This database brings together data from tree removal experiments conducted by a large number of colleagues around the world. To date, we have over 3,000 sets of individual tree data on tree from 10 countries. These include Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Latvia, New Zealand, Japan, Spain, the UK and the USA. Registered users can download the data, add new data or revise existing data. The data can be downloaded, and new data can be added, or existing data can be revised by registered users. All contributors retain ownership of their data. The data can be accessed here https://www.plantedforests.org/infrastructures/infrastructures-numeriques/tree-pulling-database/

The obligatory data for uploading to the database are “data owner”, “unique tree ID”, “tree species”, “country”, “tree diameter at breast height (dbh)”, “tree height”, “soil”, “latitude”, “longitude”, “total turning moment” and “mode of damage (break or overturn)”. There are a range of other data that can also be uploaded, and these are detailed in the upload manual.

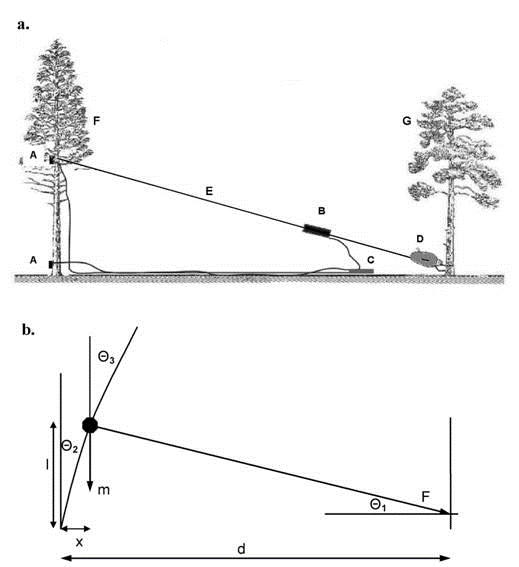

Tree pulling is the main method for determining the resistance of trees to uprooting due to the wind. The resistance is a function of tree size (usually evaluated either as stem weight, stem volume or dbh²height), species, soil type and rooting depth. The normal method is to pull the tree using a winch at a set height (typically half tree height) using a winch attached to an anchor tree (Figure 1). The subject tree is pulled towards the anchor tree (Figure 2) with the pulling cable attached to the subject tree by a nylon sling (Figure 3) with inclinometers are placed at the pull height and the base of the tree (Figure 2) to estimate the additional turning moment due to the displaced crown and stem. The tree is pulled slowly using a manual, electric (Figure 4), or motor winch until it overturns, and the maximum force applied to the tree is recorded. The key publication on this method is by Nicoll et al. (2006) and can be accessed here https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/X06-072.

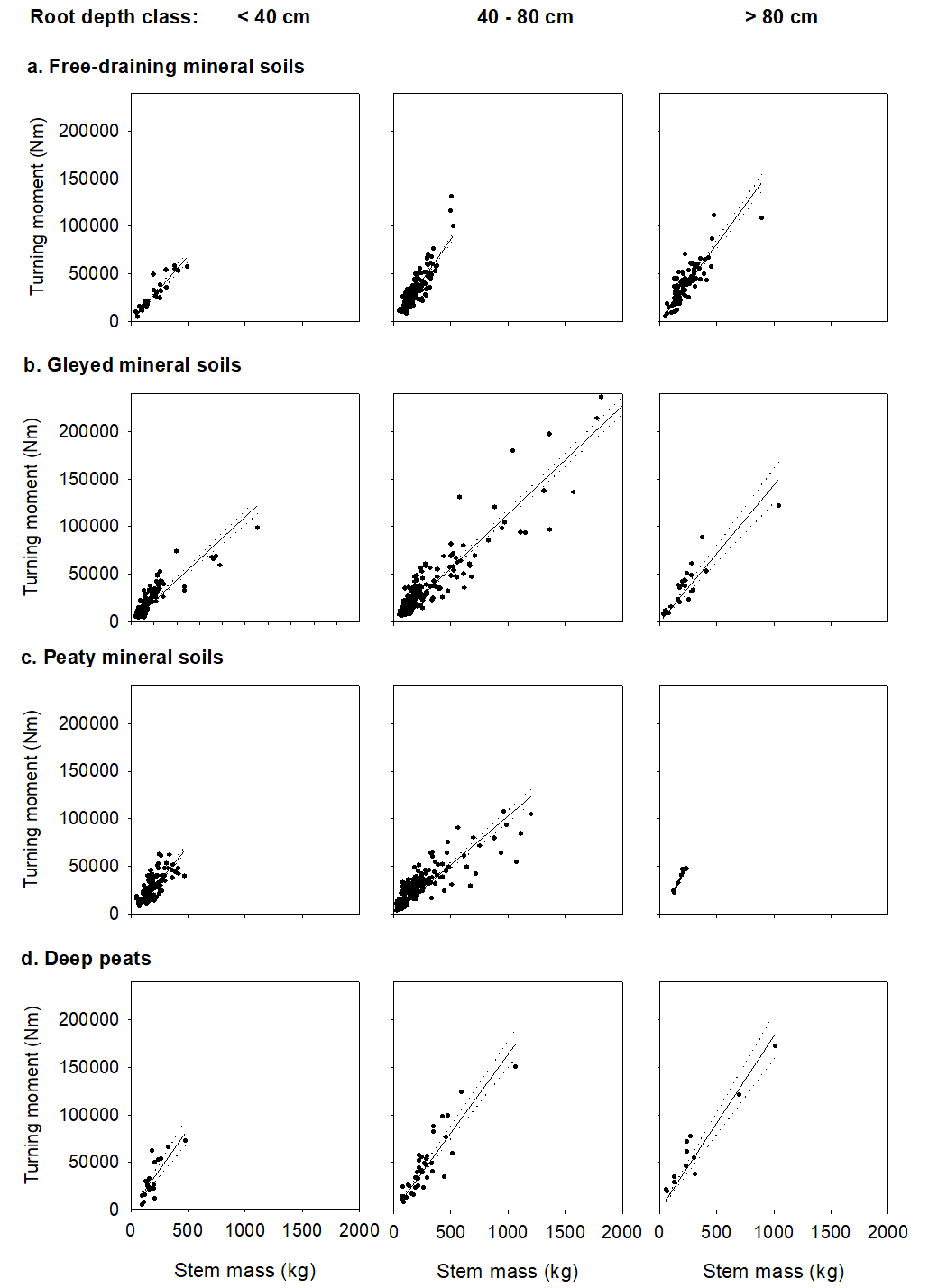

These data are then used to analyse the regression between stem weight (or stem volume or dbh²height). The slope of this regression is a key parameter (Creg) used in the ForestGALES wind risk model (Locatelli et al., 2022) that is used for determining the risk of wind damage to forest stands or individual trees in stands or tree groups (Figure 5). Information about the ForestGALES model can be found here https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/fthr/forestgales/.

We look forward to people adding their data to the database and being willing to participate in an analysis of this large unique data set. The hope is that we can determine patterns of response that will allow people to estimate the resistance of trees to uprooting in new situations (e.g. new species or soil type) without the need to necessarily conduct expensive and time-consuming pulling tests. We particularly need data on the pulling of broadleaf trees and pulling experiments from tropical regions. To contribute please contact Barry Gardiner or the IEFC.

Reference

Locatelli, T., Hale, S., Nicoll, B., & Gardiner, B. (2022). The ForestGALES wind risk model and the fgr R package (Vol. 1). https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/fthr/forestgales/

Nicoll, B. C., Gardiner, B. A., Rayner, B., & Peace, A. J. (2006). Anchorage of coniferous trees in relation to species, soil type, and rooting depth. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 36(7), 1871–1883. https://doi.org/10.1139/x06-072