From 17 to 20 October 2023, the 4th Woodrise conference gave its 4,000 participants the opportunity to exchange and share knowledge on the subject of timber construction. The plenary sessions focused on:

- Decarbonising buildings and cities with wood;

- Promoting the competitiveness of timber construction;

- Medium- and high-rise timber construction projects around the world.

The Territorial Forest Resources cluster contributed to this event by offering a workshop on the future role of plantation forests in supplying resources used in construction on an international scale.

French Situation

Stéphane Viéban, President of FCBA and Director of Alliance Forêt Bois, introduced the workshop with a fundamental question: should we adapt forest resources to the needs of industry, or adapt products to forest resources? France, like other countries, is faced with the contradictory demands of a predominantly hardwood forest and softwood products. At present, hardwoods cover 72% of France’s forest area, but account for only 24% of the volume of timber harvested and 17% of sawn timber. In 2021, plantation forests accounted for 60% of timber harvested.

France’s National Low Carbon Strategy sets out a path for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, with the aim of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. Using French timber, which has a carbon footprint 15% to 25% lower than imported products, would be one way of achieving this. In addition, the new RE2020 standard is forcing architects to pay closer attention to their carbon footprint and the origin of their raw materials, and they now want access to materials from short supply chains. Jean-Denis Forterre of FNB, presenting on behalf of Jérôme Martinez, presented the Bois de France label which certifies wood from French forests with local processing. The French industry still needs to increase its processing capacity and the quality of its sawn timber.

Processors are now having to incorporate timber from declining stands into their processes. The climatic changes that are causing this are complicating the silvicultural management applied to spruce in the Morvan or beech and oak in Picardy or Haute-Marne. These case studies, presented as examples by Jean-François Dhôte from INRAe, highlight the need to speed up forest renewal and shorten rotations to limit the risk of massive damage. Forests need to be adapted to future climates by increasing the adaptive potential of different species and renewing forest management methods by including the diversity of species, which complicates the supply to the industry.

In Scandinavia

In Finland and Sweden, adapting to climate change will involve increasing the proportion of pine species, especially in the north of Sweden, where spruce production is dominant. In these countries, forestry and its mechanisation developed considerably in the 1950s. Annika Nordin, from Stora Enso, mentioned new measures to protect biodiversity and riparian zones, and a trend towards reducing the size of clear-cuts. These new management methods often require financial assistance for owners.

In New-Zealand

New Zealand’s afforestation rate was highest in the 1990s due to high timber prices. The annual area planted then collapsed before recovering over the last 5 years. Radiata pine was the first species to be planted and now accounts for 90% of New Zealand’s plantation forest, with a 28-year rotation. New Zealand has the second highest volume of roundwood produced per capita in the world after Finland. The North Central Island accounts for 32% of the production forest by area.

Henri Baillères presented Scion’s research themes, which cover the entire industry: forestry, wood, wood-based materials and other biomaterials. New Zealand is moving towards increasing the production of processed wood and exporting higher value-added products. This strategy will require more industrial investment and an increase in the area of planted forest.

In Japan

Japan’s forest area is increasing, but the country is importing more and more timber for its own consumption. According to Yuuko Iizuka of Sumitomo Forestry, Japan’s forests are being exploited but lack maintenance due to the cost of labour and the lack of investment following typhoons. Half of the forest is over 50 years old, and heavy rainfall events are the main risk. Productivity has been improved by planting cryptomeria, but some people are allergic to it leading to hay fever. These constraints have led Sumitomo Forestry to adopt a strategy of investing in afforestation elsewhere in the world, mainly in South Asia, Oceania and North America.

In Chile

In Chile, most of the forest is temperate, but the country’s geographical configuration means that there are major differences in the situation from north to south, with a high level of endemic species. Forest plantations were first widely developed to combat erosion caused by agricultural practices that were damaging to the soil. Three major companies own 60% of the plantation forests, and the main species planted are radiata pine and eucalyptus. Paper pulp accounts for 37% of the volume produced and sawn timber for 38%. Almost all sawn timber comes from plantation forests. For Oscar Larrain, of InFor, the biotic and abiotic risks associated with Chilean forest plantations are increasing, and the plantations are becoming less and less accepted by society. To be accepted, plantation forests must form part of a heterogeneous mosaic in order to reduce their visual impact and improve their resilience.

Taking a step back

Lyndall Bull, from the FAO, provides a global perspective on the future role of plantation forests. Globally, the area of high-biodiversity forests is declining, while demand for wood products is increasing. Deforestation is falling, but reforestation is also declining, resulting in a negative global balance.

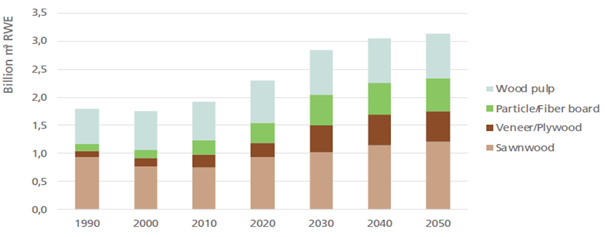

In the future, the FAO expects an increase in the use of wood in the manufacture of many products. For example, the proportion of wood used in construction is set to rise from 5% to 12% between 2020 and 2023, and from 8% to 23% in textile fibres. By 2050, 3 billion new homes will be needed, mainly in Africa, where the population is set to double. It is estimated that 33 million hectares of plantations at 15 m3/ha/year will be needed to meet the demand for wood. As a reminder, forests currently cover around 4 billion hectares worldwide. Against this backdrop, plantation forests would appear to be essential to ensure a supply of wood for the construction industry, in preference to non-renewable alternatives.

Conclusions

At present there are a number of similarities in the issues and approaches of foresters and processors around the world. Foresters must face the new challenges posed by global change by adapting their silviculture and species. Failure to act or to adapt practices will lead to silvicultural dead-ends that would be detrimental to biodiversity and human needs, including construction wood uses. The use of wood in construction will undoubtedly increase worldwide due to the significant need for housing and carbon sequestration, in response to environmental policies in various countries. These policies are also leading to greater use of wood produced with short rotations. In this context, forest plantations will play an important role in the future of forestry.

The European Institute of Planted Forests contributed to this event by financing the visit of a doctoral student via its network fund. It was in this context that Esteban Torres-Sánchez presented his thesis work, carried out at the CIF Lourizán with the University of Vigo. The project involves evaluating the addition of wood quality traits as selection criteria in Galicia’s maritime pine breeding programme. Genetic selection has already made it possible to improve the growth and straightness of Galician maritime pines, and improving wood quality could secure certain uses for them. The suitability of several families from different parents has been tested on several Galician sites. Statistics based on measurements of the performance of the different families showed that the modulus of elasticity and density could be improved from 5 families without reducing growth and straightness.

Armand Clopeau (FCBA), Christophe Orazio (IEFC)