Communication and Risk Culture: The Mental Models Approach

Faced with the growing wildfire risk in cultivated forests of southwestern Europe, the IEFC is exploring innovative preventive communication strategies based on the mental models approach. This method makes it possible to adapt prevention messages to the actual representations, practices, and knowledge of the populations concerned.

What is the “mental models” approach?

The mental models approach is based on the idea that both experts and the general public have their own vision of risk: its causes, aggravating factors, consequences, and ways to prevent or protect against it.

These lay representations are often overlooked in current awareness campaigns. However, they strongly influence behaviors depending on beliefs, misunderstandings, or false knowledge.

By identifying the gaps between the expert mental model and that of lay groups, it becomes possible to highlight key points (misconceptions/erroneous knowledge) and build clearer, more targeted, and more effective messages.

Objective: communication grounded in the reality of perceptions.

In this context, a study was conducted by the IEFC with the aim of understanding the perceptions of forest fire risk among users of the Landes de Gascogne forest.

A Rigorous Five-Step Methodology

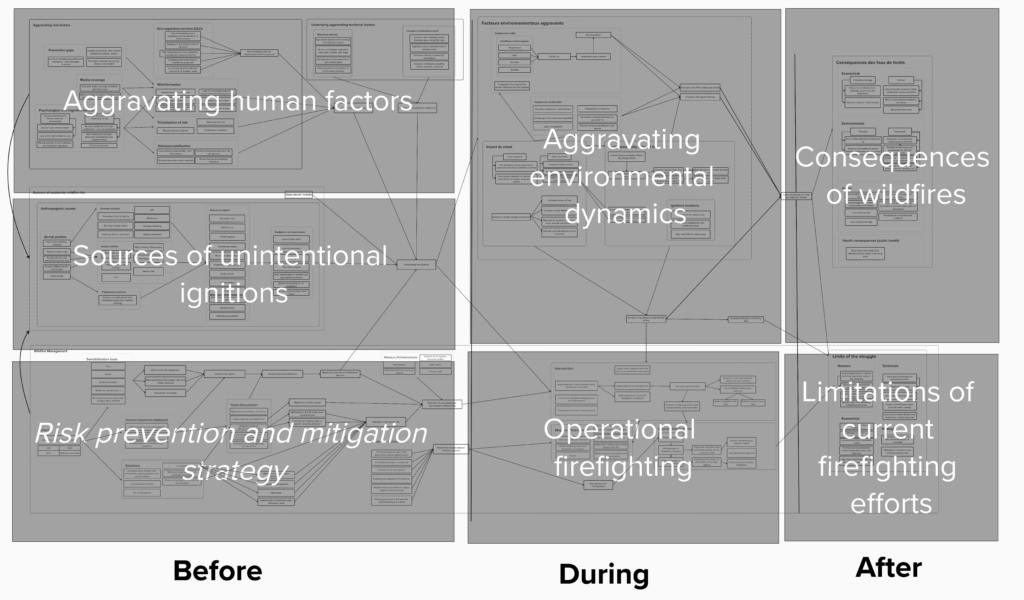

The IEFC applies a five-step methodology, transmitted by its partners—particularly ForestWize—and adapts it to the Landes de Gascogne region for relevant results.

The mental models methodology applied here has its origins in the work of Carnegie Mellon University (Morgan, Fischhoff, Bostrom & Atman, 2002), a pioneer in the comparative analysis of expert and non-expert (lay) perceptions of risk. Initially developed to improve communication on technological or environmental risks, this method has been widely validated in various contexts. Its value lies in its ability to structure, step by step, the exploration of mental representations in order to design prevention messages adapted to the cognitive and cultural realities of the target audiences.

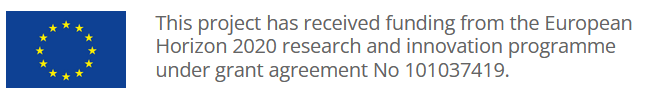

Development of the expert mental model

A review of existing literature on the subject, combined with expert interviews, enabled the precise elaboration of the components of wildfire risk in the territory.

Interviews with wildfire experts:

The IEFC conducted 10 qualitative interviews with experts involved in wildfire management or research. These exchanges made it possible to map out in detail the technical, operational, and strategic knowledge related to the risk.

The experts interviewed came from diverse structures:

- SDIS 40 (Departmental Fire and Rescue Service)

- Communes forestières des Landes (Landes forest municipalities)

- DFCI (Forest Fire Defense)

- ONF (French National Forest Office)

- DRAAF (Regional Directorate for Food, Agriculture and Forestry)

- Research institutes and PhD students

- Independent expert

Development of profane mental models

Study of at-risk lay groups :

The knowledge gathered from experts was compared with that of different population groups exposed to, or potentially involved in, accidental causes of fire:

- Recreational users: hikers, mountain bikers, hunters, fishers, motorized sports users…

- Residents in the wildland–urban interface: domestic risk activities (barbecues, DIY, burning, storage, renovation…)

- Agricultural and forestry professionals: mechanical equipment, tools, farming or silvicultural practices with fire potential

The recreational users’ mental model:

The IEFC identified convergent knowledge between experts and laypeople (represented in orange), as well as misconceptions or original contributions.

From this comparative analysis, the IEFC distinguished: shared knowledge (orange), areas of misunderstanding or mismatch (grey), and misconceptions or new insights derived from qualitative interviews with the general public.

This produced the following lay mental model:

Reinforcing the data from qualitative interviews

Following the qualitative survey with lay groups, a comprehensive—but not representative—sample was built to map out a diversity of profiles and discourses. To validate and consolidate these initial findings, a quantitative survey was developed, based on the key elements identified in the mental models.

Specific questionnaires were designed for each target group with a high level of methodological precision. Their dissemination was ensured in collaboration with the FIRE-RES Living Lab, guaranteeing strong territorial relevance and a diversity of respondents.

The results of this quantitative survey will make it possible to finalize, adjust, and strengthen the previously established mental models, ensuring their scientific robustness and their alignment with real-world contexts.

Purpose of the study

By cross-referencing these data and conducting an in-depth analysis of the interviews, the IEFC aims to clarify blind spots and formulate concrete recommendations for wildfire prevention agencies. The goal is to propose awareness methods and tools that are adapted, understandable, effective, and anchored in the reality of the populations concerned.

Results

Leasure activities :

- Representation of imagined or observed forest risk: Recreational users maintain a mostly playful and informal relationship with the forest. Their perception of wildfire risk relies more on media and collective images than on direct personal experience.

- Perceived causes of fire outbreaks: Fire is largely attributed to human behaviours considered uncivil (cigarette butts, unauthorized barbecues, littering). This moralizing view designates “others” as responsible, reinforcing individual dereliction of responsibility.

- Technical knowledge and representations: Knowledge about the risk is partial and often approximate, mixing intuition and fragmentary information without expert vocabulary. The risk is mainly associated with summer, sometimes with spring; the aggravating factors of the risk are known but the deepening of ideas remains limited.

- Perceived prevention and risk management: Institutional prevention measures are perceived as unclear, ordinary, and concentrated on critical periods. Users mainly rely on their common sense or personal experience to protect themselves.

- Perception of actors: Firefighters are the central figures, perceived positively and valued, despite identified technical limits to their actions. Other actors in management and prevention remain known but less present in discourse, and their role is little described. This idea maintains a vision centred on emergency rather than on structural prevention.

- Consequences of wildfires: Impacts are described mainly from a social, emotional or aesthetic angle (destroyed landscape, sensory shock). Economic, Environmental and health consequences are not or partially mentioned.

- Relationship to the forest and the territory: The forest is experienced as a space for relaxation, preserved nature, or play. While some express concerns, these are rarely translated into concrete changes in practices, notably due to the strong attachment to the forest.

Domestics activities :

- Risk representation linked to direct experience and emotional connection: Residents in the forest–urban interface build their perception from concrete experiences, often marked by memories of recent wildfires. Proximity to the forest fuels both attachment and concern, making risk an integrated component of daily life.

- Perceived causes of fire outbreaks: Fire is largely attributed to careless human behaviours (cigarette butts, burning, barbecues), often blamed on “bad users” such as tourists or newcomers. This moral reading reinforces individual responsibility but obscures environmental or systemic causes.

- Technical knowledge and representations: Danger is mainly associated with summer, high temperatures, and drought. The nearby forest is perceived ambivalently: a residential asset but also a source of anxiety, turning the domestic space into a vigilance zone.

- Perceived prevention and risk management: Preventive actions are highly individualized (clearing vegetation, watering, monitoring) and often based on “common sense” rather than official standards. The legal obligation to clear vegetation is known but unevenly applied.

- Perception of actors: Firefighters are perceived as central and heroic actors. Other institutional actors are little identified or criticized (absence, lack of action) despite strong expectations for protection.

- Consequences of wildfires: The impact of a fire is described mainly in sensory and emotional terms (blackened landscape, smell, fear), while socio-economic dimensions are less mentioned. Risk is experienced in an intimate rather than collective register.

- Relationship to the forest and the territory: The forest is seen both as an appreciated and cherished living environment. The territory is perceived as a mosaic of areas with varying levels of risk, without real collective dynamics, reinforcing a sense of isolation in the face of danger.

Professional activities :

- Risk representation focused on action and technique: Wildfire risk is seen primarily as a concrete issue linked to work, machine use, and individual technical vigilance. Systemic or climatic causes are rarely mentioned.

- Perceived causes of fire outbreaks: The origin of fires is mainly attributed to human factors (negligence, malicious acts) and mechanical failures. This view anchors risk in operational aspects and reinforces the idea of individual responsibility.

- Technical knowledge and representations: Professionals have precise empirical knowledge of seasonality, high-risk areas, and aggravating factors, using “expert” vocabulary. However, this understanding remains local and immediate, with few links to structural trends.

- Perceived prevention and risk management integrated into the profession: Preventive actions (machine cleaning, choice of working hours, weather monitoring) are embedded in professional routines. Collective and inter-professional prevention is little developed in discourse.

- Perception of firefighting: Firefighters are acknowledged for their effectiveness, but firefighting is viewed in technical terms (tracks, DFCI, interventions). Fire is seen as an enemy to be contained rather than as a territorial phenomenon requiring shared governance. Actors are generally known, and their roles understood.

- Consequences of wildfires: Impacts are perceived mainly in economic terms and related to professional activity (loss of worksites, professional constraints). Environmental, social, or psychological dimensions are rarely addressed, although a slight, understated emotional aspect is perceptible.

- Relationship to the forest and the territory: Strong attachment to the Landes forest, seen both as a living space and an economic resource to be protected. A predominantly productive vision, with little questioning of management practices.

- Unspoken elements: Few references are made to climate change, cooperation between actors, or the protection of populations. The mental model remains focused on immediate operationality and local control of risk.

Focused on immediate operationality and local control of risk. The qualitative survey confirmed the gaps between experts and laypeople and helped refine the mental models. For recreational and domestic users, it highlighted both shared understandings and clear divergences in how wildfire risk is perceived.

For the group of professional users, the number of responses collected was not sufficient to fully consolidate the qualitative survey results. However, this phase still made it possible to draw out several useful recommendations to better understand their needs and adapt prevention actions.